dear friends,

the world seems to be on fire – from firebombs to wildfires to dumpster fires, a relentless march of destruction of people, places, and knowledge. institutions of learning have been bombed, self-immolated, plagued by culture wars and corporate greed. same as it ever was perhaps.

i feel fortunate to be caring for books in this moment. i find they offer a wider lens (or a “longer now”) for our conversations and a community that speaks carefully and listens deeply. we’ve been making great progress on our catalog – a sneak peek below of the lists feature (and my state of mind). we’re excited to share a first version in the next month or so! the folks on this email list will be among the first people invited to try it out so please share with other book people you think might be interested.

i wrote about book links to help explore how we might rethink our digital literary sphere. i’d love to hear what you think.

glenn

the first chapter of susan orlean’s the library book begins:

Stories to Begin On (1940)

By Bacmeister, Rhoda W.

X 808 B127

Begin Now-To Enjoy Tomorrow (1951)

By Giles, Ray

362.6 G472

A Good Place to Begin (1987)

By Powell, Lawrence Clark

027.47949 P884

To Begin at the Beginning (1994)

By Copenhaver, Martin B.

230 C782

orlean starts each chapter the same way with a series of book titles and their reference codes, each relating ostensibly to the topic at hand. the result is a feeling of walking through the stacks and perusing the shelves, a form that neatly complements the story as it wanders through the LA library and the 1986 fire that consumed it. the pattern also draws attention to the book’s meta title and its own referenceability.

The Library Book (2018)

By Susan Orlean

027.4794.94

it’s a great title and works on many levels – orlean noted that it never had competitors in her mind, which was unusual for her. however, the title does have a downside: mentioning “the library book” in conversation immediately begs for clarification. it’s easy to imagine a “which book?” abbott and costello routine being kicked off by a librarian hunting down an overdue copy

of course, this problem resolves itself quickly today as we know exactly where to point to clarify what book we’re talking about: any confusion is easily dispelled with a link to our shared brain online. the proliferation of hypertext in our digital speech has transformed how we refer to media in conversation. for the most part, more ubiquitous communication helps us better understand our world together. romeo and juliet might have lived happily ever after with cell phones, for instance. however, per mcluhan, media are the message and the internet has come to consume everything that came before it, so it’s unsurprising that these links are also changing the conversation itself.

books, being some of the oldest things we still refer to today, serve as a useful case study for how the way we refer to things has changed over the centuries. the first great leap in referring to books was the title itself. when fewer books existed, readers just referred to them by their author or their first lines / incipits. if a home only had one book, they could call it “the book.” drama competitions in athens spurred the first use of titles to tell the plays apart and authors soon after began including name tags on their scrolls (aka sillybos!). the first title page popped up a millennium later in 1463 when printers were a/b testing formats for the pope’s edicts, but they didn’t catch on until the following century when the presses really heated up. since then we’ve both made a ton more books and have upped our game for how to point to them (card catalogs in the 19th century, standardized book identifiers and citational practices in the 20th). not much changed in regards to how we referenced books in conversation though. title and author covered it just fine.

however, as our conversations have gone digital so too have our citations. i notice more and more of my own talk is mediated by screens, each one outfitted with a new powerful vocabulary for referencing objects in a shared collective memory. today i use copy-pasted links to refer people to all types of things and books are no exception. if i mention anything i’m reading, i’ll reflexively follow with a hyperlink. what started as a courtesy has become more of a requirement. links went from the salt and pepper placed within reach to the silverware necessary to dig in.

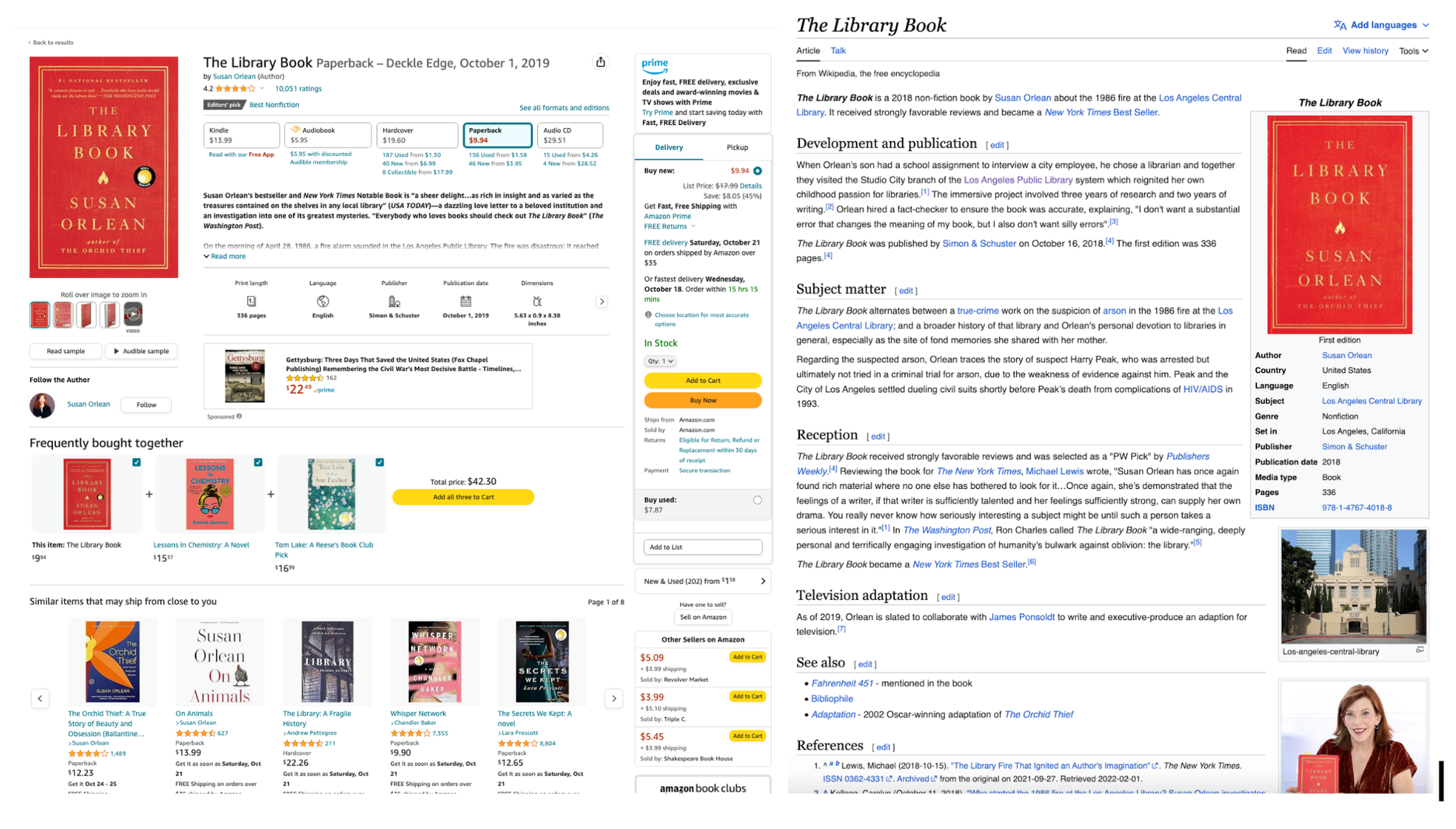

the links add context for sure — cover art, summary, page count, etc. etc. — but something also gets lost in the click. each option available feels like a poor translation, zooming in while limiting the view. for example, if i point to amazon or goodreads, the book becomes a product to buy (with star reviews, cross-sales, one-click commerce). if i point to wikipedia, it’s an artifact to be summed up. a book is both of these and more, but the click opens the box and collapses it to one.

i sense each page extending beyond the bounds of what the book is and into the grayer zone of what it means and, when it comes to meaning, books are by their nature hard to pin down. their meaning exists only in relation, defined not by the inked shapes, but the minds that make sense of them. the same words conjure something different in each of us. we can see this up close within our own experiences as different readers of the same book years apart, like how fairytales hit way different as a parent than as a child. the book changes us too, as middlemarch did to rebecca mead (an experience that became its own book). the text of a book is fixed, but its meaning is surely not.

the challenge of referencing a book lies in serving both (1) what is fixed and shared between the covers with (2) what is dynamic and meaningful outside them. titles (and names more broadly) are able to manage both – they refer to specific objects without restricting their meaning, allowing the bible or lolita to serve flexibly across different contexts and communities. i think our book links today improve on the former, but fail on the latter. they make the texts (and their details) easier to find and acquire, but they don’t care well for the full vibrant conversation about and around them. the platforms design each page for their own outcomes (e.g. sales or a single neutral summary in these examples) and are great successes by those measures. however, their choices tightly moderate what’s said and don’t serve well the conversations beyond their walls.

star ratings are a great example. the gold fractional stars that dominate book pages stamp our understanding into transactional product assessments. they ask whether a story met our goals or offered a good return on the investment of our time and money, an incredibly limited scope for how we might think to value our experience. any relational meaning is flattened further into an average. the deeply personal and interactive experience of reading is diluted to a one-dimensional stat. the stars’ social proof may help convert sales, but the generalization speaks little to the work’s place in our conversations. four star average is never what i mean when i point to orlean’s work.

the one-page-fits-all nature of book links also narrows our view. wikipedia may allow us to participate more in the results, but the imperative to agree on a single neutral perspective ultimately still constrains the symphony of experience to a single voice. what matters for me and you may be very different and we certainly lose much of what’s special to each of us in the compromise for what works for all.

with this context, it seems worthwhile to reimagine what our digital world of books could be. these critiques and others can help “make the map of the terrain” that we traverse toward alternatives. how might we instead design a book’s page as a venue for the dynamic conversation that exists between the people and media that care about it?

one place to start might be to understand each book as a network itself. there’s an existing web of authors and editors and publishers and cover artists and subjects and referrers and adapters and booksellers and librarians and critics and readers who already think and talk about the books that matter to them. they choose what books to work on, or to write reviews about (e.g. nyt, guardian), or to discuss in interviews (e.g. paris review, npr, youtube). they refer to books in conversation (e.g. about libraries) and recommend them to friends (prompted or not). they create booktoks/bookstagrams/booktubes, schedule readings in libraries, compile staff picks in bookstores, shortlist some books for prizes, and adapt others into plays. connecting this wider conversation to a shared digital home would help make these media visible to this wider community as they all care for the same object.

aaron swartz described “giving books a first class place on the web” and rory and i share that vision. in building with the open library, we hope to build new tools to care for the conversations around books, while building on the traditions of librarians, researchers, and book people who already do. we have the benefit of learning from designs that came before (shephard’s citations in law and openalex in science, google’s link of links, openlibrary and ingram catalogs, wikipedia and letterboxd’s communities, twitter and reddit’s curated feeds, etc), while taking inspiration from new aligned approaches like decentralized identifiers and decentralized social networks (eg. mastodon, activitypub, bluesky, farcaster, etc.). the technology is not the point, but the network is. the conversation around books keeps us connected to others across time and place, whether attending to the plays of athens or the 1986 la library fire. we think the web offers an opportunity to curate and preserve the ecosystem of thought around books in ways that we haven’t yet seen.